Procedural

Requirements

Effective Date: October 07, 2015

Expiration Date: October 06, 2025

|

NASA Procedural Requirements |

NPR 8831.2F Effective Date: October 07, 2015 Expiration Date: October 06, 2025 |

| | TOC | Change History | Preface | Chapter1 | Chapter2 | Chapter3 | Chapter4 | Chapter5 | Chapter6 | Chapter7 | Chapter8 | Chapter9 | Chapter10 | Chapter11 | Chapter12 | AppendixA | AppendixB | AppendixC | AppendixD | AppendixE | AppendixF | AppendixG | AppendixH | AppendixI | ALL | |

3.1.1 This chapter describes the concepts for and approach to facilities maintenance management within NASA. It describes generic facilities maintenance management system based on proven techniques. It also provides the flexibility needed at each Center for NASA's diverse, high-technology mission. The purposes of this chapter are as follows:

a. To present the methodology and value of sound facilities maintenance planning.

b. To present factors for consideration while developing a facilities maintenance organizational structure.

c. To describe the functional relationships in a facilities maintenance management system.

d. To explain methods of analyzing maintenance functions and their relationship to planning and work performance.

3.1.2 A facilities maintenance management system provides for integrated processes that give managers control over the maintenance of all facilities and collateral equipment from acquisition to disposal. The management system should provide at least the following:

a. Address all resources involved.

b. Accommodate all methods of work accomplishment.

c. Effectively interface and communicate with related and supporting systems ranging from work generation through work performance and evaluation.

d. Support each customer's mission.

e. Ensure communication with each customer.

f. Provide feedback information for analysis.

g. Reduce costs through effective maintenance planning.

h. Provide a system for accumulation of historical facilities maintenance data.

i. Incorporate RCM and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Building Design & Construction (BD&C) and O&M principles into CMMS data fields and work order processes to account for equipment criticalities.

3.1.2.1 The goal is to optimize scarce resources (workforce, equipment, material, and funds) to maintain the facilities and collateral equipment needed to support the Center's mission in a safe and efficient manner. An effective facilities maintenance management system maximizes the useful life of facilities and equipment, ensures safety of facilities and systems, minimizes unplanned downtime, and provides an improved work environment within a given resource level. It also produces information for management decisions.

3.1.3 Functional Approach

3.1.3.1 This procedure adopts a functional approach to facilities maintenance. The thrust is to identify those functions and processes required to provide an effective facilities maintenance program without specifying an organizational structure.

3.1.3.2 The following sections cover maintenance management controls, maintenance management concepts, maintenance-related functions and processes, and other factors for consideration in establishing a facilities maintenance organization. The process for establishing the maintenance organization should accommodate Center-unique requirements and conditions.

3.1.4 Mission/Customer versus Condition Approach

3.1.4.1 Facilities maintenance normally is regarded as the total responsibility of the facilities maintenance manager, who determines with what and when to accomplish maintenance based on the physical condition of the facilities and appropriate maintenance practices. With limited resources, however, the facilities maintenance manager should work with the customer to provide quality facilities maintenance services as required to support the customer's mission. The facilities maintenance manager should coordinate with the customer in developing attainable solutions to facilities maintenance-related mission-support problems.

3.1.4.2 Facilities maintenance decisions, such as whether to accomplish work now or defer it, require a knowledge and understanding of the present and future need for the facility under consideration, as well as the economic and safety impact associated with those facilities. Thus, the facilities maintenance manager should maintain perspective in evaluating necessary maintenance requirements and in considering mission criticality and the need for preserving deteriorating facilities. Both mission and customer inputs are integral components of the facilities maintenance system.

3.2.1 Facilities maintenance may be described as a number of interrelated functions and processes that directly or indirectly lead to the accomplishment of facilities maintenance work. Those functions that are not accomplished by the facilities maintenance organization are outside the responsibility of the primary users of these requirements. This also may be the case when the scope of the work exceeds applicable facilities maintenance funding or resource thresholds (e.g., CoF projects). However, functions are listed to ensure that all related services are considered when establishing a facilities maintenance organization and management system.

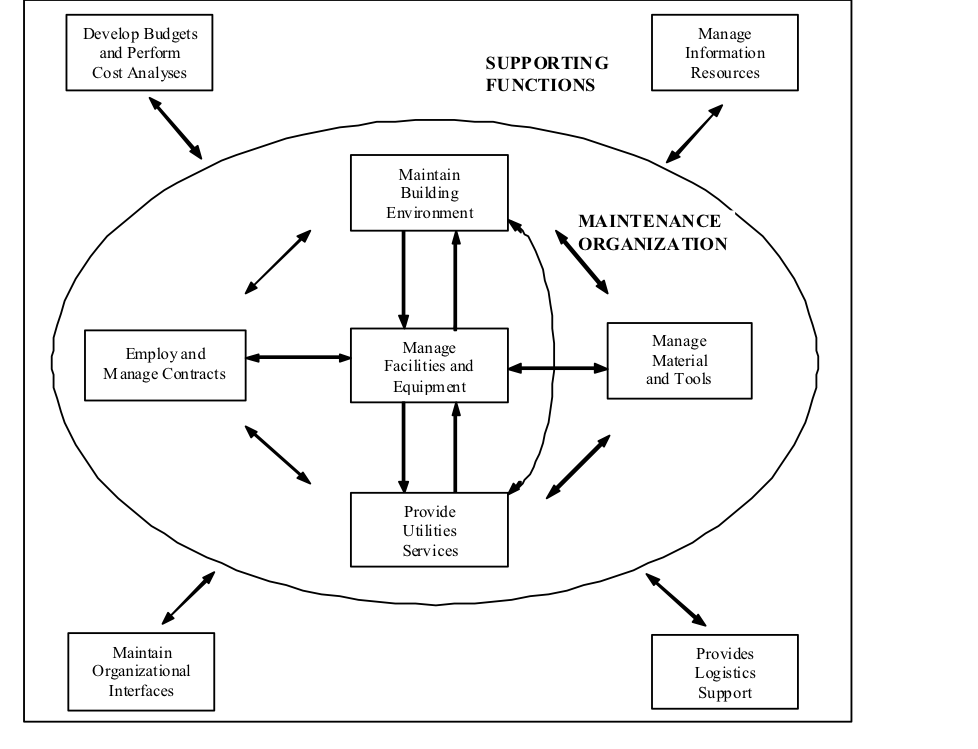

3.2.2 The relationships among the major functions related to managing facilities maintenance are depicted in Figure 3-1, Whole Maintenance Universe, along with the required information flow and internal communication. The five functional responsibilities at the core of the whole maintenance universe that reside in the Center's maintenance organization are:

a. Manage Facilities and Equipment. This includes overall management responsibilities for operations and maintenance functions regarding infrastructure systems, equipment, and components.

b. Maintain Building Environment. This is defined as the nine broadly defined systems associated with typical building occupancy (i.e., Structure, Roof, Exterior Finish, Interior Finish, Plumbing, Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC), Electrical, Conveyance (Elevators, Cranes, etc.), and Program Support Equipment). These are detailed in the annual NASA Deferred Maintenance Assessment Report generated for each NASA Center.

c. Provide Utilities Services. This includes, but is not necessarily limited to, electricity, water (potable, and non-potable), natural gas, steam, storm, and sanitary sewers.

d. Employ and Manage Contracts. This includes all contracts NASA implements for the purpose of accomplishing typical building operations and maintenance functions.

e. Manage Materials and Tools. This includes management responsibility for materials and tools necessary for conducting the building operations and maintenance functions. Particularly significant in this management area are potential environmental issues related to the use of solvents, lubricants, and various other chemicals and reactions relative to operational, maintenance, and occupancy of a building.

Figure 3-1 Whole Maintenance Universe

Figure 3-1 Whole Maintenance Universe

3.2.3 The support functions in Figure 3-1, shown outside the maintenance organization, are as follows:

3.2.3.1 Develop Budgets and Perform Cost Analyses. Although the maintenance organization performs cost analyses and develops an annual budget request, it is only an input to the Center and Agency's budget development. See section 2.4, Facilities Maintenance Budget, for the maintenance organization's budget development.

3.2.3.2 Manage Information Resources. There are a number of information resources in other organizations supporting the maintenance organization. Personnel, cost accounting, and similar staffs are required to manage a Center's maintenance operation. A major function in the maintenance organization is the management of its information systems, such as its CMMS (see Chapter 6, Facilities Maintenance Management Automation). Management of information technology (IT) systems may be performed by an IT contractor.

3.2.3.3 Provide Logistical Support. A maintenance organization requires logistical support for functions such as mobile equipment (particularly large specialized items), transportation, and vehicle fuel. It also should be provided storage for recyclable or reusable equipment and material. The maintenance organization may maintain a small warehouse for supplies and parts commonly used in its operations. Additional parts and supply support is required from the Center's logistics organization.

3.2.3.4 Maintain Organizational Interfaces. A major part of a maintenance organization's operation is its interface with other organizations. Working relationships and procedures shall be established to ensure that facilities maintenance functions are performed in an efficient and economical manner to meet Center requirements. These requirements include safety and health, legal, training, security, environmental, fire protection services, and specific requirements received in the form of TCs, service requests, and similar requests.

3.3.1 Maintenance at NASA Centers is more than just repairing a leaking pipe or restoring power. It involves the coordinated effort of many talented people to ensure that facilities are in the best possible condition to support the Center's mission. To accomplish this, the maintenance program should be managed to provide the maximum benefits from the available resources without waste.

3.3.2 A CMMS is an integral component of a Center's facilities maintenance management operations. This automated system is designed to assist facilities maintenance managers in work reception, work planning, work control, work performance, work evaluation, and work reporting. This system, discussed in Chapter 6, Facilities Maintenance Management Automation, is usually linked to other database systems, such as integrated asset program management (IAPM), material management, and personnel management.

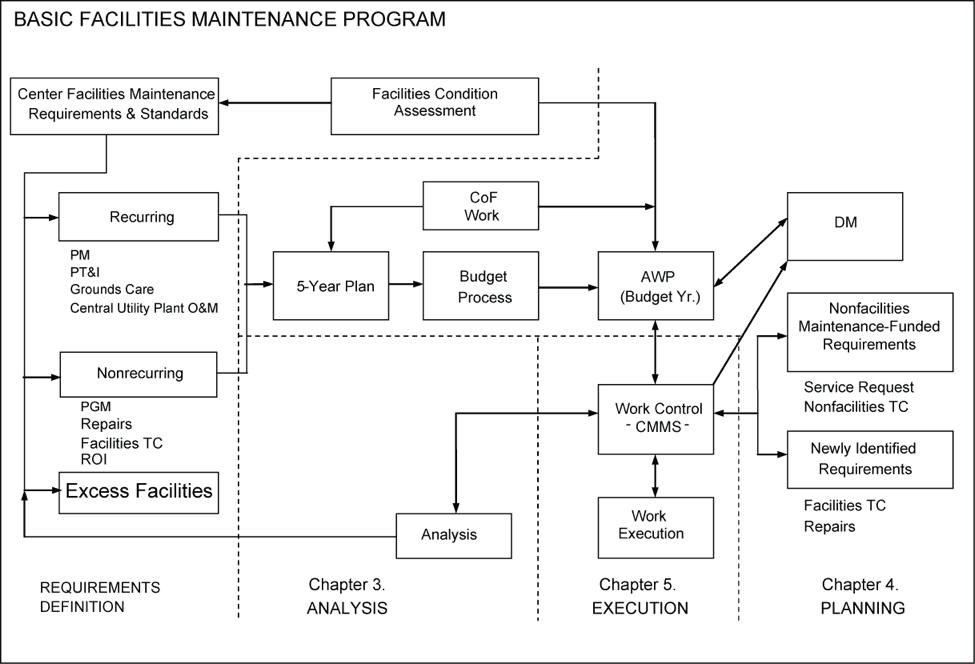

3.3.3 Figure 3-2 depicts the basic facilities maintenance management program. The program has four major aspects: requirements definition, planning, execution, and analysis. Requirements definition includes analyzing facilities condition assessments and the Center's mission to identify, quantify, and document Center operation and maintenance requirements. The Planning and Execution sections of the figure are discussed in Chapter 4, Annual Work Plan, and Chapter 5, Facilities Maintenance Program Execution. Analysis is discussed in detail in sections 3.11, Management Indicators, and 3.12, Management Analysis. The following sections briefly describe Figure 3-2 in a clockwise flow (starting at "Requirements Definition").

Figure 3-2 Basic Facilities Maintenance Program

3.3.3.1 Requirements Definition

a. Facilities Inventory. The facilities inventory is the cornerstone of facilities maintenance management. It is included in the Center Facilities Maintenance Requirements & Standards block in Figure 3-2. It provides the detailed identification of what is inspected, operated, and maintained. Without an accurate inventory, maintainable items may not receive required maintenance, and maintenance budgeting, planning, and scheduling cannot be effective. The inventory is not static; it includes continuous updates based on facility and equipment changes.

b. Recurring Maintenance. After identification of what is inspected, operated, and maintained, a Center's Reliability Centered Maintenance Program starts with identifying recurring maintenance requirements utilizing the decision logic tree shown in Figure 7-1. The requirements will be derived from analyzing the Center's mission to reflect consideration of the Mission Dependency Index and from facilities inventory and utilizing a well-established set of local standards. The standards used in assessing facilities and determining what recurring maintenance and operations effort is needed to maintain the Center at NASA's specified quality level shall include statutory, regulatory, and compliance requirements. Requirements are continually updated to include new facilities and changes based on the RCM analysis of work data provided during the acceptance process, which sets the baseline (see Chapter 8, Reliability Centered Building and Equipment Acceptance).

c. Nonrecurring Maintenance. Nonrecurring requirements are determined by facilities condition assessments and analyzing historical data, current inventory, and mission requirements. A component of nonrecurring work is facility repairs (breakdown maintenance), including facility TCs.

3.3.3.2 Planning

a. Priorities set by management based on mission requirements are important considerations in determining what is to be accomplished and in what order. The 5-Year Maintenance Plan (see section 4.6, 5-Year Facilities Maintenance Plan) is an invaluable reference for the budgeting process, providing the information needed to plan allocation of resources.

b. Upon receipt of the annual budget, the 5-Year Maintenance Plan (including the maintenance organization's CoF work) is reviewed again, together with updated facility needs. Because resources are constrained and only a portion of the needed work can be accomplished, alternative funding is obtained where possible. The remaining required maintenance work that cannot be funded in the current fiscal year is added to the DM.

c. A result of the budget process and the review is the well-documented AWP that is discussed in Chapter 4, Annual Work Plan. The AWP is used to guide the majority of the day-to-day maintenance work. The AWP also serves as a baseline reference for the facilities maintenance manager when accommodating nonfacilities and newly identified facilities maintenance requirements.

d. Throughout the planning process with the requirements, priority setting, 5-year plan, and the AWP, an essential element is requirements definition. In order for the planning to be effective and in concert with the goals of the Center, there should be continual, two-way communication between the facilities maintenance manager and the Center staff. Proper direction will ensure that maintenance work is prioritized, planned, and performed in accordance with the Center's mission goals.

3.3.3.3 Execution

a. During execution (see Chapter 5, Facilities Maintenance Program Execution), the use of the AWP as a basis for work control helps to schedule work in a steady, efficient flow pattern. The nonfacilities maintenance requirements and newly identified requirements are handled by adjusting priorities and rearranging the work-flow patterns as required.

b. In addition to performing maintenance and repair work, it is very important to document the work accomplished in the Center's CMMS and on facility drawings as necessary. This documentation, as well as historical data entered in the CMMS, is essential when analyzing the work performed and in work planning.

3.3.3.4 Analysis. The analysis section of the maintenance management program is often neglected. Proper analysis is an important management function to point out inefficiencies and ways to better execute maintenance requirements by using alternative procedures and avoiding waste. Also, analysis may identify local standards that are overly stringent for mission needs or a priority system that requires "everything to be done yesterday," thereby interrupting scheduled work unnecessarily.

3.4.1 In creating an organization and system to perform facilities maintenance, the concepts discussed in the following sections should be applied in implementing the basic maintenance program depicted in Figure 3-2.

3.4.2 Separation of Functions. The responsibility for generating, planning and estimating, and authorizing work should be separate from the responsibility for performing work. Similarly, it is preferable for the quality assurance (QA) functions to be the responsibility of an autonomous organization, apart from those ordering and performing the work. This provides the system with checks and balances and freedom from the appearance of conflict of interest.

3.4.3 Planning and Estimating. Work should be planned and estimated in enough detail to define the resources and tasks required to perform the work and to communicate this information to everyone involved. This information should be clear to customers, approving authorities, schedulers, material managers, and craft personnel.

3.4.4 Estimating Standards. Estimating standards should be the basis for work planning and estimating to permit realistic resource allocation, scheduling, work performance, and evaluation. Several commercial, industrial, and governmental standards are available to assist in work order estimating. Chapter 10, Facilities Maintenance Standards and Actions, provides information on estimating standards.

3.4.5 Workforce Load Planning. Work planning should provide a sufficient volume of work, well in advance of the required completion date, to permit balancing the facilities maintenance workload among the shops, acquiring material, arranging timely contract support, achieving priorities, and coordinating all the elements. Work should be planned on at least a quarterly basis.

3.4.6 Continuous Inspection. A program for inspection of facilities and collateral equipment should, on a timely basis, identify facilities condition, maintenance deficiencies, work required, and changing conditions. PT&I and Facilities Condition Assessment methods should be part of the continuous inspection program. Chapter 10, Facilities Maintenance Standards and Actions, provides detailed information on continuous inspection and condition assessment.

3.4.7 Five-Year Facilities Maintenance Plan. Centers should develop long-range facilities maintenance plans covering both level of effort and specific or one-time work requirements. These plans should reflect the total maintenance requirements and their prioritization in support of Center mission needs. Such management planning requires developing and justifying resource requirements on a multiyear basis. Centers shall prepare both the 5-Year Facilities Maintenance Plans and the AWPs. Chapter 4, Annual Work Plan, provides information on both of these plans.

3.4.8 Work Grouping

a. Personnel performing TCs, small service requests, and small repair jobs should be organizationally separated from personnel performing large facilities maintenance projects when possible. A suggested upper limit on the scope of these small jobs is 20 hours of effort. Assigning these small jobs to a single shop avoids interrupting the workforce devoted to PM, PT&I, PGM, and larger repair jobs. The organization of the shops or groupings within a given shop should be based on factors such as work volume, geographic proximity, availability of transportation, materials, and craft mix.

b. Work grouping also allows crafts personnel to productively complete small jobs by "batching" (i.e., providing crafts personnel with multiple TCs at once, grouping work in a particular building or area, or providing transportation with commonly used tools and materials). This reduces indirect time associated with processing small jobs (such as travel time or obtaining tools, equipment, and materials).

3.4.9 Work Scheduling. Work should be scheduled in an orderly manner considering safety, customer requirements, time constraints, material and tool/equipment availability, priority, workforce availability, and work-site availability along with necessary equipment or utility outages.

3.4.10 Work Status. The CMMS should include reporting systems that provide facilities maintenance managers the status of all work and any significant problems so they can take timely corrective action. Chapter 6, Facilities Maintenance Management Automation, discusses the use of CMMS.

3.4.11 Quality Assurance. Both Government- and contractor-performed work should be subject to inspections for quality. Quality control is the contractor's (or civil service, if applicable) program in place to ensure that the product or service meets the quality requirements of the specification or work order. QA is the Government's program that validates the product or service quality and, by extension, ensures that an effective quality control program is in place and is performing as previously approved by the Government. In performance-based contracts, written QA plans shall be prepared to guide these inspections and should be an integral part of all maintenance work. See Chapter 12, Contract Support, for detailed information on Quality Assurance Plans.

3.4.12 Condition Assessment/DM. The continuous assessment of the condition of facilities and collateral equipment coupled with the current DM defines the major portion of that total maintenance required to bring facilities up to NASA safety and condition standards. When evaluated with respect to a Center's safety and its mission requirements, the DM is a key element in management planning, budgeting, and allocating facilities maintenance resources. This process is discussed in Chapters 9, Deferred Maintenance, and 10, Facilities Maintenance Standards and Actions.

3.5.1 Physical Characteristics. The physical characteristics of a Center such as size, geographical distribution, climate, equipment, architectural style, and construction materials have a significant impact on the facilities maintenance organization. They directly affect the need for central shop spaces, remote job sites, travel time, special facilities maintenance equipment, facilities maintenance standards, and emergency response plans and equipment.

3.5.2 Mission. The mission of a Center influences the facilities maintenance organization because it determines the facilities maintenance standards, the equipment mix, the workforce skills mix, work priorities, acceptable planned and unplanned down time, and resource levels. The maintenance organization should be structured to respond to the Center's mission.

3.5.3 Workforce Composition. Workforce composition is driven in large part by the Center's mission and physical characteristics. It affects the organizational structure and the division between contract and Government workforces. For example, a workforce with a large number of electricians and A/C mechanics may dictate an organization with a separate shop for each craft. With a small workforce, these crafts may be in one shop.

3.6.1 Organizational Considerations. Organizations plan, organize, perform, control, and evaluate work. The factors in the following sections are important considerations when designing the organizational structure.

3.6.1.1 Contract Versus In-house. The proportion of the facilities maintenance work accomplished by support contractors significantly impacts the organizational structure. As the contracted portion increases, the Government workforce becomes more involved in contract administration and surveillance. The optimum mix of support contractor and Government personnel should be based on local conditions and priorities and should be consistent with the guidance contained in OMB Circular A-76 and the FAR. The principles of sound facilities maintenance management apply equally to in-house and contract work. In NASA Centers utilizing a maintenance support contractor, the contractor is a key partner in implementing and operating a successful maintenance management program.

3.6.1.2 Labor Agreements. Labor agreements may dictate certain procedures, practices, consultations, and other action. These influence the organizational structure and the Government's flexibility in making changes to the organization, work methods, or work assignments. The human resources department may provide assistance in this area.

3.6.1.3 Functional Lines. The facilities maintenance functions are vital in support of the Center's mission. Where more than one organization has responsibility for performing facilities maintenance, close coordination is necessary. The facilities maintenance organization interfaces closely, with potential for overlap, with related processes such as master planning, major facilities acquisition, and transportation and utilities management. It may be logical to organize along functional lines; however, care should be taken to ensure that lines of communication are open and maintained among all related functions and organizational elements. Senior managers should encourage communication and liaison at all levels.

3.6.2 Staffing Considerations. A number of factors will influence the staffing of a facilities maintenance organization. In cases where a PBC is utilized to perform the facilities maintenance functions, the contractor is responsible for determining the staffing and skill mix of the workforce to meet the contractual requirements. The following factors apply to staffing plan development:

3.6.2.1 Workload Balance. The facilities maintenance organization staffing should match the workload characteristics. The personnel resources available in each craft should closely match the amount of work included in the AWP, taking into consideration work priorities and alternative methods of accomplishment. Consider using temporary or part-time employees or one-time contracts to accomplish seasonal, surge, intermittent, or one-time work requirements.

3.6.2.2 Education and Training. The facilities maintenance organization should ensure that personnel have and maintain the skills needed to cope with changing technology to effectively carry out the facilities maintenance program. Skill requirements are identified through periodic reviews of all the organization workload. Comparing skill requirements with the assigned personnel skill inventory will identify shortages for correction through education, training, recruiting, or other action. Skill inventories and requirements identification should address all facilities maintenance program phases, including shop crafts, administrative skills, PT&I technologies, environmental and hazardous materials training, and the use of computers.

a. As an example, training plays a major role in reaching and maintaining skill levels required for an effective RCM program. The training should be both of a general nature and technology/equipment specific. Management and supervisory personnel benefit from training that presents an overview of the RCM process, its goals, and its methods. Technician and engineer training should include the training on specific equipment and technologies, RCM analysis, and PT&I methods.

b. RCM training is available from professional organizations, consultants, equipment manufacturers, and vendors. The following are examples of specific areas of training and possible sources for the training:

(1) Infrared thermography (IRT) is complex and difficult to measure and analyze. Training is available through infrared imaging system manufacturers and vendors.

(2) Vibration monitoring and analysis training is available from equipment vendors. The Vibration Institute has published certification guidelines.

(3) Electricians, electrical technicians, and engineers should be trained in electrical PT&I techniques, such as motor current signature analysis, motor circuit analysis, complex phase impedance, and insulation resistance readings and analysis. Equipment manufacturers and consultants specializing in electrical testing techniques provide classroom training and seminars to teach these techniques.

3.6.2.3 Licenses, Permits, and Certifications. The license, permit, or certification requirements in the following sections are applicable to Government employees and contractors. When work requiring licenses, permits, or certifications is included in a contract, the contract shall state clearly that the contractor should obtain all applicable NASA, State, and/or local government, licenses, permits, or certifications before performing the work.

a. Specialized personnel and facilities often are required to have licenses, permits, or certifications. These requirements apply to central utility plant personnel and to environmentally or safety-sensitive facilities. To the maximum extent possible, such licenses, permits, and certificates should be issued by the State or local government rather than by Centers to avoid administrative duplication. Centers should issue only those licenses, permits, and certificates that are NASA unique and, therefore, not available through other existing regulatory organizations. Detailed training and certifications requirements may be found in specific safety standards, e.g., NASA-STD-8719.9 or NASA-STD-8719.12. Additional hazardous operation safety certification requirements may be designated by each Center safety official or designee, but should include the minimum as listed in Chapter 4 of NPR 8715.3.

b. Operators of central utility plants, such as at water treatment plants, boiler plants, and wastewater treatment plants, should be licensed by applicable State and local governments. Also, when required by State or local governments, permits for such things as incinerators, licenses for other facilities maintenance-related operations such as pest control and herbicide applicators, and certificates for equipment such as pressure vessels, lifting devices, and elevators shall be obtained.

c. Maintenance Certification programs like Certified Maintenance and Reliability Professional (CMRP), is an experience-based, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) accredited certification program for maintenance and reliability professionals provided by the Society of Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP). This program was a result of the lack of consistent, well-defined standards for the body of knowledge and capabilities that maintenance and reliability practitioners should have to be effective. In addition, there was no way to differentiate those who have mastered the various elements of excellence from those who simply hold the job. (For more information go to http://www.smrp.org/files/SMRPCO%20Candidate%20Guide%20for%20Certification%20Recertification_5%209%2013.pdf .) To obtain certification candidates shall submit an application and pass a 110â??question exam. The subjects tested on the exam include:

(1) Business and Management

(2) Manufacturing Process Reliability

(3) Equipment Reliability

(4) Organization & Leadership

(5) Work Management

3.6.2.4 Federal Buildings Personnel Training Act of 2010. The Federal Buildings Personnel Training Act of 2010 (FBPTA) requires all personnel (both civil service and contractor) performing building operations and maintenance, energy management, or facilities safety and design functions to demonstrate knowledge in the core competencies identified by GSA as they apply to the individual's job. The General Services Administration (GSA) in conjunction with Department of Energy (DOE) has identified the competencies required and developed a Web-based tool for personnel to register, conduct a gap analysis on an individual's competencies and develop training requirements for that individual to become fully compliant. The tool is available at http://www.fmi.gov/ . All civil servants whose primary function is performing building operations and maintenance, energy management, facilities safety, and design should register in the system. This requirement initially focuses on civil service employees with contractor guidance to follow at a later date.

3.6.2.5 The Chief of Facilities at each NASA Center should ensure that they can meet all competencies required for their facilities within their employee and contract support competencies.

3.7.1 Everyone who works at or uses Center facilities is a customer of the facilities maintenance organization. Some are direct customers, requesting and receiving specific services such as TCs or Service Requests. Others are indirect customers, using the facilities and collateral equipment such as HVAC systems maintained by the facilities maintenance organization. Facilities maintenance, which provides institutional, as well as program support, plays a major role in keeping these customers satisfied. This does not occur automatically. Customer relations should be a primary consideration in all facilities maintenance decisions. Facilities maintenance may be the key factor in developing and maintaining the professional reputation of Center institutional managers.

3.7.2 Communication

3.7.2.1 The facilities maintenance organization cannot operate effectively without open communication. Communication is extremely important within the organization to ensure coordination of competing resources. Communication with customers and other Center entities is necessary to ensure that the correct work is accomplished at the correct time and within allocated resources. Communications between the maintenance organization and their customers should be an integral part of the CMMS. The system should provide for customer access to submit requirements and for the customers to obtain status of their requests from submittal through completion. Day-to-day communications may also utilize other Center electronic means, including e-mail and Web page access. Facilities maintenance personnel should be alert to the following barriers to communication:

a. Cryptic, incomplete work requests.

b. Misinterpreting the scope of work specified as "the supervisor wants."

c. Customers' misinterpreting technical answers to their questions on project status.

d. Differing understandings of mission needs.

3.7.2.2 Two-way communication should be encouraged, with the customer articulating customer desires and the maintenance organization providing constructive and continuous feedback through the CMMS or other electronic systems, including e-mail, where possible. This may provide an early warning of changes in workload and identify potential problems. It facilitates orderly workload planning by the facilities maintenance organization and its customers. This is particularly important during periods of limited funding because the maintenance organization often can help a customer translate desires into realistic facilities requirements, thereby obtaining an optimum solution or, at least, an adequate solution within the resources available. A well-informed maintenance organization and a "maintenance informed" Center are in a much better position to produce necessary results within available resources.

3.7.2.3 The reputation of the facilities maintenance organization is built as much on perception as on performance. A positive image of the facilities maintenance organization is created by proactive communications, i.e., keeping the customer informed about the status of the work, responding quickly to the requests, informing the customer in advance about the cost of the work, and reflecting the costs accurately in reimbursable billings and reports. The maintenance organization should have a customer liaison representative to work with each customer organization. The customer liaison should participate in the development of MOAs, AWPs, funding plans, and in the day-to-day support of the customer. However, every member of the facilities maintenance organization is an ambassador for the organization and should be sensitive to each customer's needs and perceptions.

3.7.2.4 The maintenance organization should have open communications with the following personnel and organizations:

a. Customers.

b. Health and safety.

c. Environmental office and agencies.

d. Engineering.

e. Mission personnel.

f. Center planners.

g. Support contractors.

h. Resource management personnel.

i. Local, State, and Federal regulatory agencies.

j. NASA Headquarters administrative and support offices.

k. Center Historic Preservation Officer

3.7.3 Funding Sources. The facilities maintenance organization may find that a significant portion of its work is customer funded. This is especially the case with service requests and work directly supporting R&D programs. In establishing the organizational structure, the variability, time phasing, and duration of customer-funded work should be considered. Provision should be made for estimating and managing customer-funded work. Where the level of customer-funded work is variable or cyclical, use of contracts or temporary workers may be desirable to accommodate peaks and valleys in the workload. When temporary workers are utilized, additional funding may be required to account for additional training and safety oversight.

3.7.4 Customer Mission. Customer relations should facilitate accomplishing the specific job that the customer requested. It includes understanding the customer's mission requirements and using this understanding to communicate with the customer and guide the customer's expectations. Thus, the facilities maintenance organization should understand the mission of each of its customers. This understanding will lead to better resource allocation decisions, enable the organization to meet each customer's needs, and improve the facilities maintenance organization's credibility by meeting real needs within the time and other resources available. Actually, the facilities maintenance organization's real mission is to support the Center mission using the most cost-effective means available.

3.7.5 Memorandums of Agreement

3.7.5.1 MOAs and other formalized agreements spell out support between organizations and agencies. MOAs may cover agreements between the facilities maintenance organization and other Center departments, other Federal agencies, or local governments. Typically, MOAs outline details of services provided and funding responsibilities. It is possible for a Center to be both a receiver of services from and a provider of services to another organization. These services may be provided on a reimbursable or nonreimbursable basis. Examples include provision of utilities, shared use of operational facilities such as runways, provision of fire protection services, and maintenance of special facilities such as aviation fueling systems. Examples of MOAs from other Federal agencies are training and support from the U.S. Navy and the GSA.

3.7.5.2 MOAs may offer significant advantages through better use of facilities and avoid duplication of effort. The facilities maintenance organization should be alert for opportunities to use MOAs. Where services are available under an MOA, the facilities maintenance organization would not need to dedicate organizational resources to provide the service. The increased scope of the combined service may make it possible for the provider to perform the service at a reduced unit cost to all customers by realizing economies of scale. Properly managed, the increased scope also may provide flexibility and increased capability during a time of emergency. An assessment of the impact of MOAs should be made while developing AWPs.

3.8.1 Facilities and equipment maintenance program effectiveness often depends on the support provided by other Center organizations. For example, the Office of the Chief Financial Officer may prepare budgets and allocate funds, the Office of Human Resources and Management may control staffing, the Office of Procurement may handle requests for material, and the various supporting staff offices may handle reproduction and correspondence services. Responsibility for facilities planning and engineering, including major facilities and equipment acquisition, may rest with a separate organization, such as the Facilities Engineering Office. Essential services, such as utilities, may be purchased commercially or provided by a separate Government or host activity. The facilities maintenance organization should maintain close communication and cooperation with other supporting organizations, working together to plan and manage the workload.

3.8.2 Safety and Health. It is NASA's policy to "avoid loss of life, personal injury or illness, property loss or damage, or environmental harm from any of its activities and ensure safe and healthful conditions for persons working at or visiting NASA facilities." (See NPD 8700.1.) To accomplish this, all individuals should act responsibly in matters of safety. The Center facilities maintenance organization is responsible for its role in safety by maintaining facilities in a safe condition and by performing tasks in a safe manner in accordance with NASA policy.

3.8.3 Environmental Compliance. Although environmental compliance is not typically one of the primary responsibilities of the Center facilities maintenance organization, virtually every facilities maintenance action has a potential impact on the environment. For this reason, facilities maintenance personnel should be knowledgeable about environmental requirements, adhere to applicable environmental rules and regulations, become involved to the limit of their responsibilities, and maintain open communication links with cognizant NASA environmental protection staff and regulatory officials. Environmental regulation compliance is a primary input item to establish standards.

3.8.4 Energy Management. The Center facilities maintenance organization is a prime participant in the Center's energy management program as developed in accordance with NPR 8570.1. The maintenance organization participates in identifying and is responsible for implementing O&M procedures and/or process improvements that are in the Center's Energy Efficiency and Water Conservation 5-Year Plan. Responsible maintenance organization staff members help conduct energy audits. Analysis of the Center's EMCS data will be included in the maintenance organization's planning to identify changes that indicate maintenance problems or imminent equipment or system breakdowns. All of this energy management program support should be integrated into the maintenance organization's AWP and 5-year plan.

3.8.5 Contract Support

3.8.5.1 Much of the Center facilities maintenance work is performed by contract, either by separate, specific, one-time CoF contracts; specific facilities maintenance contracts (using non-CoF funds); or support services contracts. In the case of the specific, one-time contracts, the facilities maintenance organization's responsibility is limited to initial facilities maintenance and repair requirements identification, perhaps preliminary scope definition or cost estimate preparation, observing the facility's acceptance testing (as appropriate), acceptance of initial baseline data, and resumption of the maintenance responsibility after the contract is complete. For facilities maintenance support services contracts, the facilities maintenance organization has a greater responsibility. It should be involved throughout the acquisition process in each of the following functions:

a. Determining the need for the contract.

b. Serving as a member of the acquisition team.

c. Drafting the acquisition schedule and milestones.

d. Preparing the needs analysis.

e. Writing the acquisition plan.

f. Writing the statement of work and providing plans and specifications, as required.

g. Assisting the Office of Procurement in determining the contract type.

h. Writing the quality assurance plan.

i. Conducting quality assurance surveillance during contract performance.

3.8.5.2 Close coordination with the cognizant procurement office is essential in obtaining quality services in a timely fashion. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on advance acquisition planning to ensure continuity of services.

3.8.6 Historic Preservation

3.8.6.1 For work on existing facilities with potentially historic significance, the Facilities Maintenance Manager shall contact the Center Historic Preservation Officer (HPO) for determination of historic eligibility and ensure the work complies with 36 CFR, Part 800, Protection of Historic Properties, before starting or awarding the task. The HPO will require concurrence from the State Historic Preservation Officer for major work before starting or awarding the task.

3.9.1 Initially, the maintenance organization shall know the facility activity status to establish a facility's maintenance requirement. The status may range from active to abandoned with each status requiring a different level of maintenance. (See section 3.9.5, Facility Activity Status.)

3.9.2 Information describing the facilities and collateral equipment at a Center is essential for planning facilities maintenance actions, efficiently performing facilities maintenance, documenting maintenance histories, following up on maintenance performance, energy reporting, and management reporting. Without this information, neglect of essential systems is likely, leading to inefficient operation, system failure, or loss of service.

3.9.3 With the increasing use of CMMS, obtaining the information in computer-readable format is strongly recommended. Chapter 6, Facilities Maintenance Management Automation, addresses CMMS requirements and usage.

3.9.4 Complete physical plant information consists of several databases distinguished by the type of information they contain. Chapter 6, Facilities Maintenance Management Automation, discusses databases from the perspective of facilities maintenance management automation. The following sections examine the physical plant information databases in terms of the type of information they contain.

3.9.5 Facility Activity Status. The following sections provide insight into some of the facility status classifications. Each status has its own level of maintenance required, ranging from full maintenance for an active facility to no maintenance for a facility with an abandoned status. For detailed information on maintenance requirements for each inactive facility status, see NPR 8800.15.

a. Active facility. Any facility that has a specific and present or near-term program or institutional requirement. Space utilization would normally be at least 50 percent, and/or the usage level exceeds 50 percent of the available time for use.

b. Inactive facility. Any facility that has no specific and present or near-term program or institutional requirement. The inactive facility may be placed in a "Standby," "Mothballed," or "Abandoned" status. The following generally apply to all levels of inactive facilities:

(1) No personnel occupy the facility.

(2) Utilities are curtailed, other than as required for fire, security, or safety.

(3) Facility is secured to prevent unauthorized access and injury to personnel. (4) Facility does not receive funding for renewal or other significant improvement.

3.9.6 Descriptive Data

3.9.6.1 Descriptive data is the detailed identifying information on the items to be maintained. The data falls into the following two classes:

a. Facilities data describing buildings, structures, utilities lines, and grounds improvements.

b. Collateral equipment data describing built-in equipment that is part of a facility or utilities distribution system but maintained as a separately identifiable entity.

3.9.6.2 Each separately identified and maintained item may be part of a hierarchy of systems and subsystems. For example, a motor may be a component of the water circulating subsystem of an A/C system in a facility.

3.9.6.3 Descriptive data should identify items to their related systems and subsystems. The number of hierarchical levels depends on Center requirements, but four levels of system/subsystem is the suggested minimum. For equipment, the descriptive data should include the equipment classification or grouping.

3.9.6.4 Facilities. Table 3-1 provides a list of descriptive factors and attributes used to develop a facilities database. This list is a suggested minimum for facilities management. The items on this list generally are self-explanatory.

Table 3-1 Facilities Descriptive Data

| Facility Number | Material |

| Facility Title | Finish |

| Location Status | Inspection Cycle (years) PGM Checklist/Guide No. |

| Facility Component (e.g., ceiling, door, floor, flashing, wall, drainage, parapet) | Estimated Design Life (years) Funding Source |

| Facility System (e.g., exterior, interior, roof, tank, fence, grounds) | Construction Date Condition Code |

3.9.6.5 Collateral Equipment. Table 3-2 is a list of descriptive factors and attributes used to develop a collateral equipment database. This list is a minimum for collateral equipment maintenance management. Centers with PT&I programs will have additional equipment data elements such as location of test points.

Table 3-2 Collateral Equipment Descriptive Data

| Inventory Number Nomenclature Location Building Floor Room Zone Manufacturer Vendor/Supplier Model Serial Number Date Acquired |

Estimated Life Cost Size Capacity HP Voltage Weight Current Dimensions Systems Major System Subsystem Major Component Component |

Classification Use/User Priority Funding Source PM Cycle Identifiers PM Guide No. Inspection Identifiers Condition Code |

3.9.7 Drawings

3.9.7.1 Drawings and other graphical data are a significant portion of the physical plant information, especially for buildings, structures, utilities systems, real estate, and land improvements. They also may be a significant portion of the available information for equipment in the form of shop drawings, schematics, photographs, and assembly drawings. Drawings may exist in many forms, including paper, photographs (such as microfilm, microfiche, and aperture cards), video images, and computerized data. Computerized forms include Computer-Aided Design and Drafting (CADD), Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Building Information Model (BIM), or vector-based drawings. Drawings may be linked to work orders through a CMMS database.

3.9.7.2 Significant challenges in drawing management include keeping drawings up to date, maintaining an indexed library of drawings, and maintaining a linkage between the drawings and the systems they represent. To the maximum extent possible, Centers should require all drawings for new or modified facilities and equipment to be delivered to the Government in computer-readable and revisable form. However, the wholesale conversion of existing drawings to computerized form may not be practical. All drawings should be filed and retained in accordance with guidance provided in NPR 1441.1.

3.10.1 It is necessary to gather facilities and collateral equipment data to support the facilities maintenance program.

3.10.2 Existing Databases

3.10.2.1 Existing databases maintained by the Center provide a starting point for developing an inventory of maintainable facilities and collateral equipment items. However, databases developed for other purposes, such as financial accounting, will not identify all maintainable items, systems, subsystems, and components. Further, they may include items not relevant for facilities maintenance management purposes. Using these databases as a starting point requires screening entries for inclusion in the facilities maintenance database. Where a unified Center database exists, this might take the form of flagging records as part of the facilities maintenance management program. Where the existing data is in a computerized database, it also may be possible to arrange for electronic transfer of portions of the data. This may simplify loading the data into the facilities maintenance management database. Potential existing databases include the NASA Real Property Management System and Center-unique industrial plant, personal, and minor property or collateral equipment inventory systems.

3.10.2.2 Creation of separate databases with common data elements carries the risk of having conflicting data. If separate databases are created, a methodology should be developed and implemented to update the data from one database to the others to avoid inconsistencies.

3.10.3 Physical Inventory. A physical inventory may be necessary to verify the data imported from other databases and to gather supplemental information to identify maintainable items and their associated systems, subsystems, and components not previously inventoried. Identification tags placed on collateral equipment during the inventory will help to ensure that all maintainable collateral equipment is picked up for entry into the database. Using identification tags also helps to avoid duplication.

3.10.3.1 In-house. It is possible to perform a complete physical inventory using in-house workforce as part of the continuous inspection and PM programs. However, this effort may take a long time and could result in the diversion of a significant portion of the facilities maintenance workforce, thereby adversely impacting routine facilities maintenance.

3.10.3.2 Contract. Contracting for the inventory is an effective method of obtaining the data. The contract may be a separate action, in conjunction with a comprehensive condition assessment, or it may be part of the development of Maintenance Support Information. (See section 10.9, Maintenance Support Information.)

3.10.3.3 Inventory Maintenance. Once developed, the facilities and collateral equipment inventory requires continuous updating to reflect additions, deletions, or changes to the physical plant. Normally, this effort is part of the continuing inspection program.

3.10.3.4 Identification Tags. Equipment identification tags should be clearly visible. Using permanent, machine-readable tags, such as preprinted bar code labels, eases maintenance and inventory automation and reduces the potential for data-entry errors.

3.10.4 User Information. Equipment users or custodians also are a source of inventory information as they receive new equipment or determine that equipment they already have requires maintenance. The initial identification typically will take the form of a request for equipment installation or maintenance. It may also be a response to a call for inventory assistance from the facilities maintenance organization. In either case, the information provided may not be enough for facilities maintenance management purposes. A field investigation may be necessary to obtain all of the maintenance information.

3.11.1 Section 3.11.5, Work Element Relationships, discusses the total facilities maintenance effort and relationships among the individual work-element efforts. However, there are a number of other relationships typically used in the facilities maintenance community for indicating the effectiveness of the facilities maintenance operation and for comparing current performance with goals and objectives. These relationships are called management indicators, performance measures, or simply "metrics."

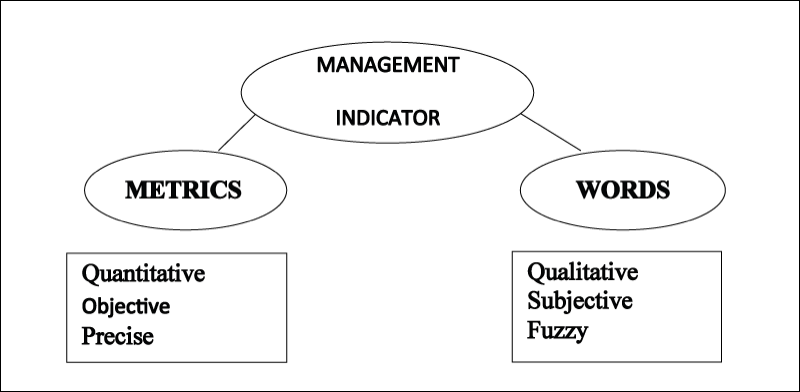

3.11.2 As shown in Figure 3-3, management indicators may be expressed as words (such as "outstanding" or "excellent") or numbers (metrics). Current management theory holds that one cannot manage an operation effectively unless one measures it. Metrics are preferable to word descriptions because they may be trended more easily. Also, they tend to be more precise and objective than words. Regardless of what metrics are used by individual Centers, some system of measurement is vital to the process of continuous improvement.

Figure 3-3 Management Indicators

3.11.3 NASA's policy is to continuously improve technical and managerial processes to minimize life-cycle maintenance and repair costs. One process to use is benchmarking. Using benchmarking and its related metrics, Center facilities maintenance managers can evaluate maintenance performance, compare performance against maintenance standards, and identify trends. This process will help managers in identifying and implementing best practices and can provide a basis for performance projections to be used in preparing the AWP and the Center's 5-Year Plan.

3.11.4 The following sections provide a general definition of a metric, its components, and its attributes. They also discuss the role metrics play in the continuous improvement processes and present examples of metrics used by facilities maintenance organizations.

3.11.5 Work Element Relationships

3.11.5.1 There are relationships among the facilities maintenance work elements that indicate the strengths and weaknesses of a facilities maintenance program. Table 3-3 shows typical ranges of effort for the principal work elements at a large physical plant of diverse age and complexity.

Table 3-3 Work Element Percentages and Indicators

| Work Element* | Average Range as Percentage of Total Work Effort |

|---|---|

| Preventive Maintenance (PM). | 15â?"18 |

| Predictive Testing & Inspection (PT&I). | 10â?"12 |

| Programmed Maintenance (PGM). | 25â?"30 |

| Repair (other than TC). | 15â?"20 |

| Trouble Calls (TC). | 5â?"10 |

| Replacement of Obsolete Items (ROI). | 15â?"20 |

| Service Requests (SR). | 0â?"5 |

| ----------- | |

| Total | 100% |

| Key performance indicators for facilities maintenance. | |

| Facility Condition Index (FCI): Upward trend (Agency-wide goal of 4.0). | |

| DM: Downward trend. | |

| Planned Work (PM, PT & I, PGM, and some ROI): Upward trend. | |

| Unplanned Work (TC, Emergency Repairs, some ROI): Downward trend. |

3.11.5.2 The percentages in Table 3-3 apply to the total facilities maintenance effort. The percentage ranges are guides only. For example, if repairs exceed 20 percent by a significant amount, it may indicate that more effort should be put into PM, PT&I, and PGM. Likewise, if TCs exceed 10 percent, it may indicate that PM and PT&I effort should be increased. The greatest effort, 50 to 60 percent, should be applied to PM, PT&I, and PGM. The limit on service request work is suggested only because of the potential for a large amount of service request work to detract from the maintenance effort.

3.11.5.3 The ranges in Table 3-3 are recommended as a basis for self-evaluation until each Center accumulates sufficient data to reflect its unique situation. Thereafter, analysis should be based on the relationships appropriate to the Center.

3.11.5.4 Two of the work elements do not appear in Table 3-3: Central Utility Plant Maintenance and Operations and Grounds Care. Both depend on local circumstances and vary too widely to estimate a meaningful range.

3.11.5.5 As a general rule, the percentage of work authorized by work order should increase, the percentage of scheduled work should increase, and the percentage of unscheduled work should decrease.

3.11.5.6 Metrics Definition

a. Metrics are meaningful measures. For a measure to be meaningful, it should present data that encourages the right action. The data should be customer oriented and be related to and support one or more organizational objectives. Metrics foster process understanding and motivate action to continually improve the way a process is performed. This is what sets metrics apart from measurement. Measurement does not necessarily result in process improvement. Effective metrics always will. Projecting this improvement, metrics can be used in preparing a Center's AWP and 5-Year Plan.

b. A more useful definition for managers is that a metric is a measurement that is made repeatedly at prescribed intervals and that provides vital information to management about trends in the performance of a process or activity or in the use of a resource.

c. Each metric consists of a descriptor and a benchmark. A descriptor is a word description of the units used in the metric. A benchmark is a numerical value of the metric or the limits within which the metric is to be kept that management selects as the goal against which the measured value of the metric is compared. For example, a typical metric is the ratio of planned maintenance work (dollars) over total maintenance work (dollars) expressed as a percentage and shown in the following equation:

Planned Maintenance Work (dollars)

Total Planned Work (dollars)

d. The planned maintenance work and total planned maintenance work are the descriptors, the units of which are dollars. In the example, 80 percent is the goal or benchmark.

3.11.5.7 Metrics Attributes

a. Metrics have common attributes that should be considered when they are being developed. A good metric has many of the following attributes:

(1) It is customer oriented.

(2) It is linked to a goal or objective.

(3) It is process/action oriented.

(4) It distinguishes good from bad or desirable from undesirable results.

(5) It is derived from data that is readily collectable.

(6) It is trendable.

(7) It is repeatable.

(8) It is simple.

(9) It expresses realistic/achievable goals.

b. Customer orientation is important because the ultimate success of facilities maintenance services is partly dependent on how they are perceived by the customer. A metric should be action oriented, which means that the organization should have the capability to change the metric parameters. Just as what cannot be measured cannot be managed effectively, there is no need to measure what cannot be controlled. A metric should distinguish good from bad, which again is based on a standard or goal, i.e., movement toward the goal is good, and conversely, movement away from the goal is bad. The data for the metric should be collectable, preferably already contained within the accounting system or the CMMS. A metric should be trendable so that successive readings can be compared with meaningful results. It should be simple, so that those who use it, carry it out, or are affected by it can understand it. Finally, the metric should be realistic. If it is clearly not achievable, workers will not strive to achieve it.

3.11.5.8 Metrics' Role in Continuous Improvement

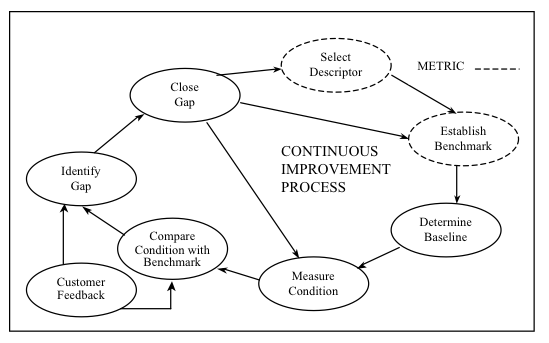

a. The role of metrics in the continuous improvement process is illustrated in Figure 3-4. This figure illustrates the simple closed loop in any management system. The first step is to select the descriptor and establish the benchmark, which together make up the metric. Establishment of the metric should consider the factors listed in section 3.11.5.7, Metrics Attributes.

Figure 3-4 Continuous Improvement Process

b. When the metric is implemented, management should establish the baseline, i.e., where the organization is with respect to the benchmark. Preferably, this information is known, at least approximately, and used when setting the goal (benchmark). Then management can develop a system to measure and report the descriptor condition regularly over uniform periods of time (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly). The measured value is compared with the benchmark to identify the gap between the two. Management then acts to close the gap. After several iterations, it may become apparent that either the descriptor is not appropriate or the benchmark is unrealistic. If this is the case, the metric should be revised and a new baseline determined. If the original metric is both suitable and realistic, the measurement cycle should be repeated with the gap between the benchmark and the measured value becoming progressively smaller. In this situation, true continuous improvement is occurring.

3.11.5.9 Benchmarking. Two organizations that promote the use of metrics for continual improvement are the American Productivity and Quality Council (APQC) and the American Society for Quality (ASQ). While the APQC's emphasis is on benchmarking, the ASQ promotes customer satisfaction as the means to achieve continuous improvement. One of the best methods for achieving continuous facilities maintenance improvement is using metrics with benchmarking. Benchmarking is the process of continuously identifying, measuring, and comparing processes, products, or services against those of recognized leaders to achieve superior performance.

a. Objectives. The objectives of benchmarking are as follows:

(1) Accelerate the change process.

(2) Achieve both incremental and breakthrough improvements.

(3) Achieve greater customer satisfaction.

(4) Learn from the best to avoid reinventing (applying lessons learned).

(5) Apply best practices using the latest feasible technology.

b. Types of Benchmarking:

(1) Internal. A comparison of internal operations, for example, within a Center or NASA-wide.

(2) Competitive. A competitor-to-competitor functional comparison.

(3) Functional. A comparison of similar functions within NASA Centers or with industry leaders.

(4) Generic. A comparison of functions or processes that are the same regardless of Center or industry.

c. Approaches to Benchmarking. The NASA approach found to be successful has been generic benchmarking using the hybrid approach. Benchmarking approaches are as follows:

(1) Centralized. Managed by a single corporate entity, e.g., by NASA Headquarters.

(2) Decentralized. Managed at the local level, e.g., by individual Centers.

(3) Hybrid. A combination of the centralized and decentralized approaches.

d. Facilities Maintenance Management Indicators:

(1) The benchmark depends on the Center baseline and goal or objective. More important, a specific metric by itself is the recognition of its usefulness in proactively establishing patterns, trends, and correlation with other data to describe past, current, and anticipated conditions. Center maintenance managers should utilize metrics continuously to evaluate the effectiveness of their management.

(2) A major benefit of the metric information is its evaluation over several periods to obtain trends. Metrics may be maintained visually using graphs, bar charts, or other methods. The periods may be monthly, quarterly, annually, or by contract evaluation period. The benchmark of "Local" means that the individual Center should establish its own benchmarks based on experience and look for improvement trends and irregularities.

(3) The metrics presented in Appendix G should be used by Center maintenance managers for evaluating various maintenance areas on a continual basis. Individual metrics can refer to the maintenance organization as a whole or by individual shops, crafts, contracts, or subcontracts. These are essentially tools for facilities maintenance managers in evaluation of their operations and for providing NASA Headquarters metrics data.

3.11.5.10 Examples

a. Center Metrics. Metrics can be classified using categories, such as facility condition, work performance, work elements, budget execution, and many others. Examples shown in Table 3-4 are some of the metrics that are recommended for Center self assessments. These and additional metrics that might be utilized in evaluating a maintenance program and benchmarks are contained in Appendix G. The corresponding WBS codes also are provided in Appendix G.

b. Center Facilities Maintenance Functional Performance Metrics Summary Sheet. Table 3-4 is the metrics sheet. The Center's metrics data shown in the table is usually submitted to NASA Headquarters in November of each year. The following sections provide additional insight into the metrics data shown in the table.

Table 3-4 Sample Management Metrics

CALCULATED from DATA PROVIDED |

||

FYxx Center Facilities Maintenance Functional Performance Metrics Summary |

||

AGENCY PARAMETRIC MEASURES | UNIT | |

| FYxx Facilities Deferred Maintenance (DM) | $M | |

| FYxx Current Replacement Value (CRV from FYxx DMA Report) | $M | |

| FYxx Facility Condition Index (FCI) | # | |

DATA INPUT FROM CENTERS |

||

| 1 | Unconstrained Maint. and Repair (M&R) Requirement, FYxx (w/out CoF) | $M |

| 2 | Initial Operating Plan for Maintenance & Repair (M&R), FYxx | $M |

| 3 | Actual Annual Maintenance and Repair (M&R) Funding (Without CoF) | $M |

| 4 | Cost of Scheduled Work | $M |

| 5 | Cost of Unscheduled Work and Breakdown Repair | $M |

| 6 | Number of PT&I "Finds" | # |

| 7 | Repair Cost of PT&I "Finds" | $M |

| 8 | Unfunded Cost to Repair Breakdowns/Failures | $M |

| 9 | Number of Trouble Calls | # |

| 10 | Reportable Incident Rate (RIR) | # |

| 11 | Lost Workday Case Incident Rate (LWCIR) | # |

| a. | Scheduled Maintenance Cost as a percentage of Total Maintenance Cost | $M |

| b. | Unscheduled Repair Cost as a percentage of Total Maintenance Cost | $M |

| c. | FYxx Total Site CRV | $M |

| d. | Initial Operating Plan as a percentage of CRV | % |

| e. | Maintenance and Repair Funding as a percentage of CRV | % |

| f. | Cost of Deferred Maintenance as a percentage of CRV | % |

ENERGY/UTILITY USAGE METRICS (HQ Energy Manager) |

||

| 12 | Energy Used/Consumed | MWH |

| 13 | Water Used/Consumed | Gal |

| 14 | Natural Gas and Oil Used/Consumed | Cu Ft |

Note: Additional Benchmarks for metrics are in Appendix G.

| $B | Billions of Dollars |

| CoF | Construction of Facilities |

| DM | Deferred Maintenance |

| FSM | Facilities Sustainment Model |

| LWCIR | Lost Workday Case Incident Rate (aka DART, Days Away, Restricted, and Job Transfer) |

| $M | Millions of Dollars |

| M&R | Maintenance and Repair |

| MWH | Megawatt Hour |

| PGM | Programmed Maintenance |

| PM | Preventive Maintenance |

| PT&I | Predictive Testing and Inspection |

| RIR | Reportable Incident Rate |

| ROI | Replacement of Obsolete Items |

| TC | Trouble Call |

Abbreviations:

$B = billions of dollars; $M = millions of dollars; CoF = Construction of Facilities; DM = Deferred Maintenance; Lost Workday Case Incident Rate (aka DART, Days Away, Restricted, and Job Transfer); M&R = Maintenance and Repair; MWH = Megawatt Hour; PGM = Programmed Maintenance; PT&I = Predictive Testing and Inspection; RIR = Reportable Incident Rate; ROI = Replacement of Obsolete Items; TC = Trouble Call; # = Number.

Notes:

| 1 | The unconstrained Center-level funding including PGM, PM, PT&I, ROI, TC, and non-CoF repair amount that represents a manager's reasonable estimate of the full annual requirement that would maintain the Center's facility inventory in a "good commercial" level of condition, while not allowing DM to grow further, and providing a level of reliability that the supported programs find acceptable for their missions. A minor amount of DM reduction could be included in this figure. |

| 2 | Initial Operating Plan for annual center-level maintenance & repair funding consisting of PGM, PM, PT&I, ROI, non-CoF repair, and TC. |

| 3 | Annual Center-level M&R funding including PGM, PM, PT&I, ROI, TC, and non-CoF repair. |

| 4 | Scheduled Work consisting of PGM, PM, PT&I, ROI, and PT&I "Finds" repair costs. |

| 5 | Unscheduled Work, typically Repair and TC costs. |

| 6 | The Number of PT&I Finds. |

| 7 | The annual cost to repair PT&I Finds. |

| 8 | The annual Unfunded Cost Estimate to Repair Breakdowns / Failures |

| 9 | The annual Number of Trouble Calls |

| 10 | Reportable Incident Rate during FYxx for O&M and support services contracts. RIR = (Total annual # of injuries incurred x 200,000)/(Total annual # of hours worked). |

| 11 | Lost Workday Case Incident Rate during FYxx for O&M and support services contracts. LWCIR represents the number of injuries and illnesses per 100 full-time equivalent workers and calculated as: (N/EH) x 200,000, where N = the number of injuries and illnesses, EH = the total hours worked by all employees during the calendar year, and 200,000 is the base for 100 equivalent full-time workers (working 40 hours per week, 50 weeks per year). |

3.12.1 The maintenance requirements at each of the NASA Centers change continually, as does the maintenance technology. As a result, maintenance programs should be analyzed periodically at both micro and macro levels by facilities maintenance managers. These analyses should be based on personal observations of work being performed, customer feedback, reports (informal and formal), supervisor evaluation, metrics evaluations, and reports from the CMMS.

3.12.2 Performance Review. Facilities maintenance managers should review the performance indicators periodically to evaluate progress and readjust the maintenance program. Performance reviews may be formal or informal, based on the needs of the organization and the personal style of the manager. The manager analyzes the information contained in the metrics and, when available, the information provided through benchmarking. The manager's performance reviews should consider how to improve the way of doing business rather than continuing to operate in the old ways. The lessons learned from benchmarking often are helpful in determining the actions that should be taken as a result of performance reviews. The following are candidate areas to review:

a. Standards of maintenance may require modification because of changing mission requirements or changes in the use of facilities.

b. New maintenance techniques or materials may provide savings, thereby enabling additional work to be accomplished within the same level of resources.

c. Initial priorities may be set higher than necessary because of incorrect perceptions, lack of management preparation, or lack of insight, which may result in expediting work unnecessarily. This, in turn, may lead to worker inefficiency and extra management and supervisory effort.

3.12.3 Cost Avoidance. Cost-avoidance opportunities are not always obvious from the day-to-day observation of maintenance operations. When looking at the costs to maintain or repair a facility, the manager and all maintenance personnel should consider measures to avoid facility damage or equipment breakdown. Cost-avoidance action seeks to eliminate all maintenance efforts resulting from inefficiencies, misdirection, and mismanagement. Also, customers should recognize their role in optimizing the expenditure of maintenance funds. Most individuals take reasonable care of the facilities they use; however, waste may result when proper consideration is not given to the care and use of facility assets. The following factors, while not new ideas, should be considered in identifying cost-avoidance measures:

a. Preventing facility damage.

b. Minimizing wear and tear on facilities.

c. Eliminating the waste of energy.

d. Recognizing opportunities for multiple use or ways to reuse excess or underutilized facilities.

e. Eliminating, containing, or controlling hazardous material contamination with its consequent impact on the use of facilities.

3.12.4 Productivity Enhancements. Facilities maintenance productivity may be enhanced by actions such as the following:

a. Improving customer feedback to reduce customer calls to management for information.

b. Using a priority system that enables workers to complete one job before starting another.

c. Empowering maintenance personnel to report problems when found and changes to facilities or equipment otherwise not known (e.g., customer-made changes).

d. Reviewing data-entry procedures to ensure that different personnel do not enter data several times into different systems.

e. Reviewing work-order execution times to identify wasted labor caused by material, transportation, or support delays.

f. Monitoring to look for improved scheduling and travel consolidation efficiencies.

3.12.4.1 Two major detriments to productivity enhancements are excessive reporting without reason and the natural tendency to resist change.

3.12.4.2 One of the most important productivity enhancers is keeping personnel well motivated and encouraging a sense of ownership toward the facilities. This applies for both Government and contractor personnel.

3.12.5 Alternative Procedures. Maintenance and repair work does not decrease when resources are scarce. On the contrary, more items tend to be deferred, and the maintenance problems grow worse. Accordingly, efforts should be devoted to finding alternative methods to accomplish the same results. The following should be considered:

a. PT&I technology with remote sensing of equipment status replacing periodic, on-site manual inspection and reporting.

b. Increasing PM crew capabilities to reduce the number of separate crews required to perform maintenance on a particular item of equipment.

c. Replacing scheduled PMs with PT&I schedules. Process improvement/reengineering.

3.12.6 AWP Monitoring. The program analysis depicted in Figure 3-2 not only refers to management indicators but also refers to the AWP since it is the baseline or guide for the year's work. The plan should be updated with new information as appropriate. The following questions should be asked when comparing actual performance with the AWP:

a. Is the organization within budget?

b. What is the cause of any budget variances?

c. Is scheduled maintenance being performed on schedule?

d. Should RCM root-cause analysis be applied to any identified problem?

e. Were there any significant emergencies?

f. Is productivity improving? Is it being hampered by institutional factors?

g. Have there been any mission changes affecting facilities?

h. Has there been any customer changes affecting facilities?

i. What customer feedback has been received?

3.12.7 Performance Indicator Use. The performance indicators discussed in section 3.11, Management Indicators, only are beneficial when they are analyzed by management for use in improving the total program. These may be broken down into internal and external indicators as follows:

a. Internal indicators are those where the information is all directly available to the facilities maintenance manager and the indicators assist the manager in improving operations. A sample of these indicators is shown in Table 3-5. Most of these indicators evaluate timeliness, efficiency, and maintenance effectiveness.

Table 3-5 Internal Performance Indicators

| Indicator | Performance Measured |

| Average Duration of Work Order Processing | Processing Timeliness |

| Actual Work Order Cost versus Estimated Work Order Cost | Performance Efficiency |

| Completion Date versus Estimated Date | Timeliness |

| Emergency Trouble Call Response Time | Responsiveness |

| Routine Trouble Call Response Time | Responsiveness |

| Equipment Availability Rate | RCM Effectiveness |

| Mean Time Between Equipment Breakdown | RCM Effectiveness |

| Percentage of Overdue PMs at End of Month | RCM Management Effectiveness |